The evolution of trees and forests in the Middle to Late Devonian Period, 393–359 million years ago, profoundly transformed the terrestrial environment and atmosphere. The oldest fossil trees belong to the class Cladoxylopsida. In general, their water-conducting system was a ring of hundreds of individual strands of xylem (water-conducting cells) that were interconnected in many places. However, how these structures grew and how the trees became tall enough to make a forest are still unclear.

Researchers from the Nanjing Institute of Geology and Palaeontology of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (NIGPAS), Cardiff University (UK) and the State University of New York at Binghamton (USA) report exceptionally well-preserved fossil tree trunks approximately 374 million years old from Xinjiang, Northwest China. These fossils suggest that earth’s earliest forest trees were able to achieve great size by a unique method that involved building a hollow cylindrical skeleton of interconnected, growing, woody strands that both tore itself apart and collapsed under its own weight in a controlled manner as the tree’s diameter expanded. The finding was published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS) on Oct. 23.

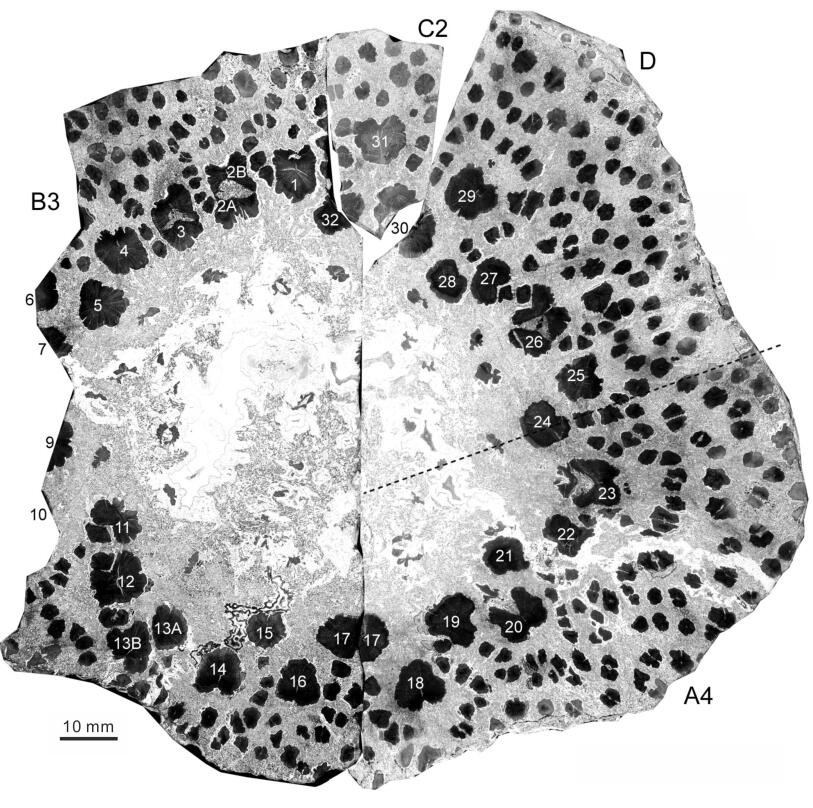

Cladoxylopsida included the earliest large trees that formed critical components of globally transformative pioneering forest ecosystems in the Middle and early Late Devonian (ca. 393–372 Ma). Well-known cladoxylopsid fossils include the up to ∼1-m-diameter sandstone casts known from Middle Devonian strata in New York State. The cladoxylopsid trunk structure comprised a more or less distinct cylinder of numerous separate cauline xylem strands connected internally with a network of medullary xylem strands and, near the base, externally with downward-growing roots, all embedded within parenchyma. However, the means by which this complex vascular system was able to grow to a large diameter is unknown.

In this research, a team of scientists led by Dr. XU Honghe from NIGPAS carried out a theoretical study on how earliest trees grow, based on exceptional, up to ∼70-cm diameter silicified fossil trunks with extensive preservation of cellular anatomy from the early Late Devonian (Frasnian, ca. 374 Ma) in Tacheng, Xinjiang in northwest China.

Xinjiang trunk expansion is associated with a cylindrical zone of diffuse secondary growth within ground and cortical parenchyma and with production of a large amount of wood containing rays and growth increments produced by normal cambria, both surrounding individual xylem strands. The xylem system accommodates expansion by tearing individual strand interconnections during secondary development. This mode of growth seems capable of producing trees of large size. Understanding the structure and growth of cladoxylopsids informs the analysis of canopy competition within early forests with the potential to drive global processes.

The study has been published online: Xu H-H, Berry CM, Stein W, Wang Y, Tang P, Fu Q. 2017. Unique growth strategy in the Earth’s first trees revealed in silicified fossil trunks from China. PNAS.

The largest silicified trunk in the field, with a maximum diameter of ∼70 cm, from the Upper Devonian of Xinjiang, Northwest China.

The transverse plane of a trunk from the Upper Devonian of Xinjiang. Note at least 33 cauline xylem strands forming a double cylinder, with some in the process of dividing. Letters indicate the different slices; numbers indicate the cauline strands.